Pardon the alarmist tone of the title, but I just don't think folks are paying a whole lot of attention to the way that technology is being used these days in writing instruction. I alluded to this in my earlier post on informating vs. automating technologies. Perhaps I was being too circumspect.

Jeff, Mike & I said that the robots are coming.

The response has been...well...quiet (I get that a lot).

But let me tell you what I think is happening right now that bears more than just quiet contemplation. It has to do with automating technology, but more importantly, it has to do with what I see as a fundamentally flawed understanding of how people - especially young people - learn to write. The idea is a simple one: you can learn to write alone. And that we can figure out a way to give "personalized" feedback to individual learners.

The

thought is that, as with other subjects, students work alone and get

some kind of automated feedback on progress that serves to customize

their process. It is, to my eye, a return to the very things we in

the computers & writing community fought so very hard to escape

from in the days when the popular term was Computer-Assisted-Instruction. Individualized

drills. Now with more adaptive smarts. But the thought is the same:

students working alone can learn to write better.

Now, let me be very very clear about this next point. All the research we know of says this isn't true. Please don't believe me. Believe Graham & Perin's 2007 metanalysis or Kellog & Whiteford's comprehensive synthesis of the available research. Read it, though, and then consider that lots of folks

are heading down a path that either explicitly (bad) or implicitly

(worse) sees learning to write as a solo activity.

As teachers and researchers, we see this trend as bad for students. Folks like recently retired MIT Professor Les Perelman do too...saying that teaching students how to do well on a written exam scored by a machine, or by hundreds of readers acting like a machine, is not the same as teaching them how to write well.

We must stop teaching this way and running our programs this way. That *includes* training a bunch of human raters to score writing based on adherence to holistic criteria. Yes, you heard me. It's time to stop all that.

I've been thinking a lot about this issue of "calibration"

lately in connection with the rising popularity of individualized learning. I'll try to keep this short and clear: the way we

are used to doing calibration reviews - norming readers to find specific traits in a text - is good at showing

agreement (or lack of) about the features present in a single text. But these reviews

cannot show agreement about where criteria are best

exemplified across multiple acts of writing. What we really want to know is whether students can write well whenever they need to, and whether they can meet each new exigence with a repertoire that allows them to do that.

In other words: our current practice with holistic scoring is to settle for

agreement about the features of a text rather than agreement about the

criteria and their application more broadly. It is, I think

most of my colleagues would agree upon reflection, an example of settling for a less powerful

indicator of learning because the more desirable one was

formerly out of reach. It was simply not practical to see, with precision and rigor, students engage learning outcomes in writing across multiple instances of writing, reading, and review. So we had to settle for one high-stakes performance.

But not any more. Now we have Eli.(stay with me, this is not a sales pitch)

With Eli, we can run a calibration round "in reverse." That is, we can ask students to find the best fit

between criteria and a group of essays. Using criteria

matching and/or scaled items in Eli, "best fit" essays are nominated

by the group. As the review progresses, a teacher can check to see if she/he agrees with the highly

rated examples. This is an inductive approach to calibration. And it not only produces judgements about how/if student raters recognize features that match criteria, but whether and how they *produce* these features as a matter of routine (shown by a group trend) or whether one, a few, or the whole group needs more practice.

If a highly nominated text turns out to be something a teacher also rates highly, what you have is a much stronger and

more reliable indicator of learning than

the deductive approach gives us. You have a portrait of the way students have deployed the criteria as a principle in their own writing and in their judgement of others' writing. The deductive method can produce a valid result

for a single text, but as Perelman notes it is not a terribly reliable way to tell us who can write, again, in another situation with similar success.

Conversely, in an Eli review where agreement between the raters and the teacher is weak, the instructor has a very, very clear signal

regarding where there is confusion about how students are able to apply the

criteria. This allows for targeted instruction and a much more

effective next intervention.

So here is a simple claim that is, nonetheless, a bold one: Eli is better at calibration.

Why? We offer a way - for the first time - to focus on calibrating on the criteria, not on a sample

text. The informating technology built into Eli handles the extra work of comparing

agreement across multiple texts, something that we might well

do by hand if it weren't so arduous. We therefore get a valid

and reliable result that also guides instruction in a much

more focused way. We also avoid the problem of implicitly

asking students to reproduce the formal features of the sample

text rather than creating an original draft that exemplifies

the criteria (an old problem with the progymnasmatum

known as

imitatio).

This is a big shift. But it is profound because it shifts us back to the human-driven activity of learning to write. We have settled for too long on a method that is best left to robots. It was always a compromise. But we don't have to settle for it any longer.

I said this wasn't a sales pitch. I mean it. If you are inspired by this post to try Eli, get in touch. We'll work something out.

This is an occasional blog where I write about teaching, technology, and that I occasionally invite others to do the same when I am teaching the AL 881 Teaching with Technology course at MSU.

Wednesday, November 6, 2013

Friday, August 2, 2013

Informated Teaching & Learning

It's been nearly 25 years since Shosana Zuboff published In the Age of the Smart Machine: The Future of Work and Power and introduced the term "informate" as a contrast to "automate" to describe how technology transforms work and working conditions. To automate is to consciously and systematically transfer both the skill and the responsibility for routine work practice from a human to a non-human agent. To informate is to enroll a non-human agent in work practice such that it provides feedback to the human agent.

I've written a lot about informating technologies in my career as they apply to writing, knowledge work, and to the knowledge work of teaching writing. That last topic is something I care deeply about as a teacher of writing myself. With Tim Peeples, I wrote a chapter called "Techniques, Technology, and the Deskilling of Rhetoric & Composition: Managing the Knowledge-Intensive Work of Writing Instruction." In that chapter, Tim & I warned that the costs of writing instruction were so high that we would soon see technologies arise to automate as much of the work associated with it as possible. Automated grading, outsourcing, and other things were part of this gloomy forecast. Worst of all, we argued, student learning would suffer.

But we saw another way too, suggested by Zuboff's alternative path, to create informating technologies that not only improved working conditions for teachers but also helped to demonstrate, via the information generated, that our pedagogies were working. To demonstrate, in other words, that students were learning.

Tim & I first presented the work that informed that chapter when we were still graduate students. And it was a bit strange looking out into a crowd of experienced faculty and issuing what surely seemed, at the time, to be dire warnings and equally Quixotic exhortations that we must immediately get to work building new kinds of software, new writing systems oriented toward learning. I've done that a lot in my career too.

But here lately, with help from my colleagues at WIDE, I've started to act on that call. We even have a little company now. We make software that informates teaching and learning. We do this as a deliberate, emphatic alternative to those making software that automates teaching and learning. We do this because we think it serves learners better. And we know it serves teachers better too.

I wanted to say this - as plainly and clearly as I could - because I am guessing some of you would like to know what we are up to and why when we talk to you about Eli. So that's it. What and why. We think learning to teach writing well is tough but it is worth it because it is the best way to help students understand themselves as learners as well as writers. We think helping students to understand themselves as learners - not merely as writers trying to get a paper done - is hard work, but well worth it too.

There are many others out there making software that does exactly the sort of thing Tim & I predicted all those years ago. If you read that post I linked to, you won't recognize the names of folks working on that software as rhetoric and writing studies scholars. You WILL recognize the names of the companies funding those projects as the same folks that buy you hors d'oeuvres at the 4C's. I am not happy that this prediction has come true. But I am doing something about it. You can too.

I've written a lot about informating technologies in my career as they apply to writing, knowledge work, and to the knowledge work of teaching writing. That last topic is something I care deeply about as a teacher of writing myself. With Tim Peeples, I wrote a chapter called "Techniques, Technology, and the Deskilling of Rhetoric & Composition: Managing the Knowledge-Intensive Work of Writing Instruction." In that chapter, Tim & I warned that the costs of writing instruction were so high that we would soon see technologies arise to automate as much of the work associated with it as possible. Automated grading, outsourcing, and other things were part of this gloomy forecast. Worst of all, we argued, student learning would suffer.

But we saw another way too, suggested by Zuboff's alternative path, to create informating technologies that not only improved working conditions for teachers but also helped to demonstrate, via the information generated, that our pedagogies were working. To demonstrate, in other words, that students were learning.

Tim & I first presented the work that informed that chapter when we were still graduate students. And it was a bit strange looking out into a crowd of experienced faculty and issuing what surely seemed, at the time, to be dire warnings and equally Quixotic exhortations that we must immediately get to work building new kinds of software, new writing systems oriented toward learning. I've done that a lot in my career too.

But here lately, with help from my colleagues at WIDE, I've started to act on that call. We even have a little company now. We make software that informates teaching and learning. We do this as a deliberate, emphatic alternative to those making software that automates teaching and learning. We do this because we think it serves learners better. And we know it serves teachers better too.

I wanted to say this - as plainly and clearly as I could - because I am guessing some of you would like to know what we are up to and why when we talk to you about Eli. So that's it. What and why. We think learning to teach writing well is tough but it is worth it because it is the best way to help students understand themselves as learners as well as writers. We think helping students to understand themselves as learners - not merely as writers trying to get a paper done - is hard work, but well worth it too.

There are many others out there making software that does exactly the sort of thing Tim & I predicted all those years ago. If you read that post I linked to, you won't recognize the names of folks working on that software as rhetoric and writing studies scholars. You WILL recognize the names of the companies funding those projects as the same folks that buy you hors d'oeuvres at the 4C's. I am not happy that this prediction has come true. But I am doing something about it. You can too.

Wednesday, July 31, 2013

Inviting Eli to Your Class

I am thrilled that this Fall semester, many fellow teachers will be

using Eli Review in their classrooms for the first time. Thanks for giving it a try! We are excited to help out in any way that we can. Our colleagues often ask Jeff, Mike, & I "how do we get the best results using Eli right

from the start?" In this post, I’ll answer that by suggesting a couple of ways of

thinking about Eli as a new resource. And I’ll also suggest a few specific things to do

to help you see the value of Eli right away.

1. Think of Eli as a window on students’ writing and reviewing process

It’s true that Eli is a service that streamlines the process of doing peer review. Students can easily exchange work and offer feedback to one another, guided by teachers’ prompts. But Eli is not merely meant to streamline workflow during review.

Eli allows teachers to set up write, review, and revise cycles and track students’ progress through them. This means that Eli is a service that supports all of writing instruction, not just that bit in the middle where students’ review each other’s work. Two things follow from this, for me, as a teacher. One is when in the process I give writers feedback. With Eli, my guidance comes after each writer has

1) shared a draft in Eli (write)

2) received feedback from peers (review) and

3) compiled their feedback and a reflection in a revision plan (revise)

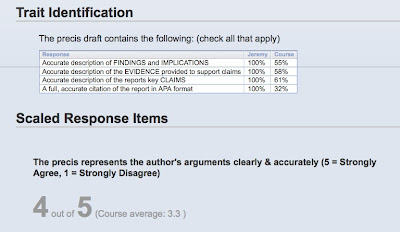

I still read each students’ draft, but now I also have a much clearer idea what they are planning to do next because I can see their revision plan and feedback. As a result, my feedback is more focused: I can adjust their revision priorities if need be, or simply encourage them to go ahead with a solid plan if they have one. To illustrate, let’s look at a snapshot from an individual students’ review report. Eli shows me how the student did and how he compares with the rest of the group. This student we will call “Jeremy” is doing rather well:

When I look at these results and read his draft, I know what to say to Jeremy. What would you say?

The second thing is that now, for a typical assignment, I might do 4 or 5 Write-Review-Revise cycles. I start with something short, like a prompt for the student to do a one paragraph "pitch" that glosses their key argument and supporting evidence for an argumentative essay. Next I might ask students to submit a precis' that summarizes a key secondary source. Third we might look at a "line of argument" or detailed outline. Fourth is a full draft in rough form.

The prompts for reviewers in each cycle would ask students to focus on matters appropriate to that stage of the writing process. So we would leave matters of attributing source materials accurately in MLA style until cycle four, but we would address accurate paraphrasing in cycle two when students are preparing a precis.

I usually try to have one or two cycles per week in a typical course, which is enough to keep students focused on drafting, reviewing, and revising consistently throughout a project (as opposed to doing everything at the end).

2. Think of Eli as a means to adjust your teaching priorities on the fly

So what do multiple cycles, each with a detailed review report buy you as a teacher? Something nearly magical happens when, during a review, I make sure that I explicitly align my learning goals for a particular project with the review response prompts I give to students.

Here’s what the magic looks like. The data below come from reviewers’ combined responses to two scaled items – like survey questions – that I included as part of a review of rough drafts of an analytic essay.

Note that the prompts are things I hope to see my students doing by this point. These are things we've been talking about and practicing in class. Seeing these results, I know what to spend more time on. Not everybody is using secondary source material well just yet. But I also see which students are doing well. I'll have them lead our discussion.

But how do we get from a writing assignment to a review that gives me this kind of real-time feedback to guide instructional priorities? Let's go through that process using a writing assignment - a real one from a course my colleague was teaching called "Writing and the Environment." This is a prompt for one of the short weekly response papers students were asked to write:

Write a response to the chapters from Walden by Emerson. Your response should consider the work itself as well as the historical context of the message. What did it mean for Emerson to write this book? to write it when he did? These should not be simple summaries of the essays/chapter. Instead they should be a comment on what YOU THINK and/or FEEL in response to the week’s texts. What main ideas stuck with you and why? What questions did they raise for you? What made you wonder? Did you agree, disagree? Were you inspired, angered, encouraged, surprised?

Thinking ahead to the review report we want to see as the instructor – the one that aggregates information for the whole class – we are interested to know which response papers have the traits mentioned in the assignment description above. These traits match up with my colleauge's learning goals for this particular point in the course. She wanted students to engage Emerson's text not only as a work of creative non-fiction, but as part of an evolving, historical dialogue in the U.S. that has shaped our understanding of the environment and society's relationship(s) to it.

So one of the key learning outcomes for the Emerson weekly response is related to seeing Emerson's writing as a product of its time and as an influence on what came after. Another is less specific to that week and that particular reading because it applies to all of the readings, and it is the ability to not merely sum up what was said, but to explain how the views of the writer changed over the course of the narrative (and to attribute those changes to the writers' experiences).

So, with these goals in mind, I’ll set up the review prompt like this:

Read the essay and check the box to indicate if the writer has done the following things:

You might be wondering, at this point, "where's the revision part of this cycle?" Well, for these short response papers, which help students process readings, we might not ask for revised versions to be turned in. But if I'm the instructor, I'd still use the revision plan task in Eli anyway, like this:

Revision Plan Prompt

You will have a chance to write on this topic again for your synthesis essay. Gather the feedback that was most helpful for you from the peer review round and reflect on the ways you might re-read Emerson, do additional research, or revise your responses. Write a note to your future self about what you can do to score well on the exam with a similar writing task.

Once students have submitted their revision plans, what I see, as the teacher, is a set of materials that includes their original draft, all the feedback they received from peers, all the feedback they gave to others, and their revision plan with reflections on what they can improve upon in their next opportunity to write about Emerson. This is what I comment on, offering advice that adjusts or reinforces priorities to help them focus on the areas of greatest need.

A final thought: Write, Review, Revise…Repeat!

With Eli, my approach to teaching writing has not really changed very much. But my execution - my ability to see, understand, and offer feedback on students' writing process has improved dramatically. I make more decisions and give more feedback based on evidence than I did in the past.

Students’ work during peer review, on the other hand, changes tremendously with Eli. It is, quite simply, far better. So are their revision plans and revised drafts. With better (and more) feedback, I see better writing. It is that simple.

1. Think of Eli as a window on students’ writing and reviewing process

It’s true that Eli is a service that streamlines the process of doing peer review. Students can easily exchange work and offer feedback to one another, guided by teachers’ prompts. But Eli is not merely meant to streamline workflow during review.

Eli allows teachers to set up write, review, and revise cycles and track students’ progress through them. This means that Eli is a service that supports all of writing instruction, not just that bit in the middle where students’ review each other’s work. Two things follow from this, for me, as a teacher. One is when in the process I give writers feedback. With Eli, my guidance comes after each writer has

1) shared a draft in Eli (write)

2) received feedback from peers (review) and

3) compiled their feedback and a reflection in a revision plan (revise)

I still read each students’ draft, but now I also have a much clearer idea what they are planning to do next because I can see their revision plan and feedback. As a result, my feedback is more focused: I can adjust their revision priorities if need be, or simply encourage them to go ahead with a solid plan if they have one. To illustrate, let’s look at a snapshot from an individual students’ review report. Eli shows me how the student did and how he compares with the rest of the group. This student we will call “Jeremy” is doing rather well:

The second thing is that now, for a typical assignment, I might do 4 or 5 Write-Review-Revise cycles. I start with something short, like a prompt for the student to do a one paragraph "pitch" that glosses their key argument and supporting evidence for an argumentative essay. Next I might ask students to submit a precis' that summarizes a key secondary source. Third we might look at a "line of argument" or detailed outline. Fourth is a full draft in rough form.

The prompts for reviewers in each cycle would ask students to focus on matters appropriate to that stage of the writing process. So we would leave matters of attributing source materials accurately in MLA style until cycle four, but we would address accurate paraphrasing in cycle two when students are preparing a precis.

I usually try to have one or two cycles per week in a typical course, which is enough to keep students focused on drafting, reviewing, and revising consistently throughout a project (as opposed to doing everything at the end).

2. Think of Eli as a means to adjust your teaching priorities on the fly

So what do multiple cycles, each with a detailed review report buy you as a teacher? Something nearly magical happens when, during a review, I make sure that I explicitly align my learning goals for a particular project with the review response prompts I give to students.

Here’s what the magic looks like. The data below come from reviewers’ combined responses to two scaled items – like survey questions – that I included as part of a review of rough drafts of an analytic essay.

Note that the prompts are things I hope to see my students doing by this point. These are things we've been talking about and practicing in class. Seeing these results, I know what to spend more time on. Not everybody is using secondary source material well just yet. But I also see which students are doing well. I'll have them lead our discussion.

But how do we get from a writing assignment to a review that gives me this kind of real-time feedback to guide instructional priorities? Let's go through that process using a writing assignment - a real one from a course my colleague was teaching called "Writing and the Environment." This is a prompt for one of the short weekly response papers students were asked to write:

Write a response to the chapters from Walden by Emerson. Your response should consider the work itself as well as the historical context of the message. What did it mean for Emerson to write this book? to write it when he did? These should not be simple summaries of the essays/chapter. Instead they should be a comment on what YOU THINK and/or FEEL in response to the week’s texts. What main ideas stuck with you and why? What questions did they raise for you? What made you wonder? Did you agree, disagree? Were you inspired, angered, encouraged, surprised?

Thinking ahead to the review report we want to see as the instructor – the one that aggregates information for the whole class – we are interested to know which response papers have the traits mentioned in the assignment description above. These traits match up with my colleauge's learning goals for this particular point in the course. She wanted students to engage Emerson's text not only as a work of creative non-fiction, but as part of an evolving, historical dialogue in the U.S. that has shaped our understanding of the environment and society's relationship(s) to it.

So one of the key learning outcomes for the Emerson weekly response is related to seeing Emerson's writing as a product of its time and as an influence on what came after. Another is less specific to that week and that particular reading because it applies to all of the readings, and it is the ability to not merely sum up what was said, but to explain how the views of the writer changed over the course of the narrative (and to attribute those changes to the writers' experiences).

So, with these goals in mind, I’ll set up the review prompt like this:

Read the essay and check the box to indicate if the writer has done the following things:

- include facts that accurately place the work in its historical context

- explain the change(s) in perspective the author underwent

- explain the experiences Emerson had that inspired his thinking

- include thoughts of the writer (not only a summary of Emerson's thoughts)

You might be wondering, at this point, "where's the revision part of this cycle?" Well, for these short response papers, which help students process readings, we might not ask for revised versions to be turned in. But if I'm the instructor, I'd still use the revision plan task in Eli anyway, like this:

Revision Plan Prompt

You will have a chance to write on this topic again for your synthesis essay. Gather the feedback that was most helpful for you from the peer review round and reflect on the ways you might re-read Emerson, do additional research, or revise your responses. Write a note to your future self about what you can do to score well on the exam with a similar writing task.

Once students have submitted their revision plans, what I see, as the teacher, is a set of materials that includes their original draft, all the feedback they received from peers, all the feedback they gave to others, and their revision plan with reflections on what they can improve upon in their next opportunity to write about Emerson. This is what I comment on, offering advice that adjusts or reinforces priorities to help them focus on the areas of greatest need.

A final thought: Write, Review, Revise…Repeat!

With Eli, my approach to teaching writing has not really changed very much. But my execution - my ability to see, understand, and offer feedback on students' writing process has improved dramatically. I make more decisions and give more feedback based on evidence than I did in the past.

Students’ work during peer review, on the other hand, changes tremendously with Eli. It is, quite simply, far better. So are their revision plans and revised drafts. With better (and more) feedback, I see better writing. It is that simple.

Thursday, May 16, 2013

Eli and The Evidence: How I Use Review Results to Guide Deliberate Practice

Recently, I traveled to Washington State University to talk with faculty there about writing, learning to write, and what the evidence says is the best way to encourage student learning. You can find lots of the material for both the full-day workshop and my University address on the Multimodal blog published by the Writing Program.

In my talk, I reviewed some of the powerful evidence that shows what works in writing instruction: deliberate practice, guided by an expert (teacher), and scaffolded by peer feedback (Kellogg & Whiteford, 2009). But I also urged teachers to be guided by the kind of evidence that emerges from their own classrooms when students share their work. This is not simply doing what peer-reviewed studies say works, but involves systematically evaluating what the students in your classroom need and responding to that as well.

This can be a challenge to do. The evidence we need to make good pedagogical choices for the whole group, or to tailor feedback for a particular student, does not collect itself.

This is why we built Eli! With Eli, instructors can gather information shared by students during a peer review session to learn how the group - and how each individual student - is doing relative to the learning goals for a particular project or for the course as a whole.

A Review Report in Eli

Our marketing partner, Bedford St. Martin's, has put together some great resources designed to help instructors get the most out of Eli. And one especially helpful discussion that I'd like to point out here shows what evidence a review report makes available and how it might be used to guide deliberate practice in writing. Here's what a teacher's review report looks like in Eli:

Because Eli aggregates the results of review feedback into one report, a teacher can see trends that are helpful for providing various kinds of feedback to students. Here, I'll talk about just one kind of feedback - trait matching - and how it can be useful in the context of deliberate practice. I'll also offer some examples from my own pedagogy to show why having evidence is so powerful.

Help Students Identify Revision Priorities by Noting Missing Traits or Qualities

One type of feedback that students can give one another is called "trait matching" in Eli. Reviewers check boxes to indicate whether a specific feature is present in the draft. When I'm teaching, I use trait matching items to help students zero in on what is most important at a particular stage in their drafting process. Early on, for instance, it might be a main idea or thesis. Later on, it might be supporting details to develop an argument more fully.

In the review report, then, I get a result like this:

This tells me what percentage of reviewed drafts contained the four traits I have specified should be in each one. Notice that in this summary, most writers have included a summary of their own media use patterns. But fewer writers have made references to two secondary sources in these drafts.

This helps me to identify what I need to emphasize to the whole group, and it also allows me to evaluate each individual student's revision priorities as reflected in their revision plans (also in Eli). I know that at least 44% of those plans should list references to secondary sources!

Here's how I might convey these trends to students. First, I will reassure them that the patterns they've noticed agree with my own reading of their work. This let's them know that they can trust the feedback they are receiving from their peers:

Next, I'll try to interpret a bit and even pull out some good examples that they identified during their reviews (and which I think everyone can learn from):

Of course, these are just my comments to the whole group. For individual students, I can drill down further and say something like this:

Thanks for providing a wonderful example of using evidence to support a claim. You are using primary source data well in this draft! Now, work on putting your primary source data in comparison with the secondary source - the trends reported in the Pew Internet report. Are your media use patterns similar or different than others' in your age group as reported by Pew?

Having this evidence makes all the difference when it comes to getting students to see a writing assignment as a way to identify what kinds of writing moves they need to improve (vs. those that they are doing well) and to practice those things in a deliberate way.

References

Kellogg, R. T., & Whiteford, A. P. (2009). Training advanced writing skills: The case for deliberate practice. Educational Psychologies, 44(4), 250–266.

In my talk, I reviewed some of the powerful evidence that shows what works in writing instruction: deliberate practice, guided by an expert (teacher), and scaffolded by peer feedback (Kellogg & Whiteford, 2009). But I also urged teachers to be guided by the kind of evidence that emerges from their own classrooms when students share their work. This is not simply doing what peer-reviewed studies say works, but involves systematically evaluating what the students in your classroom need and responding to that as well.

This can be a challenge to do. The evidence we need to make good pedagogical choices for the whole group, or to tailor feedback for a particular student, does not collect itself.

This is why we built Eli! With Eli, instructors can gather information shared by students during a peer review session to learn how the group - and how each individual student - is doing relative to the learning goals for a particular project or for the course as a whole.

A Review Report in Eli

Our marketing partner, Bedford St. Martin's, has put together some great resources designed to help instructors get the most out of Eli. And one especially helpful discussion that I'd like to point out here shows what evidence a review report makes available and how it might be used to guide deliberate practice in writing. Here's what a teacher's review report looks like in Eli:

Because Eli aggregates the results of review feedback into one report, a teacher can see trends that are helpful for providing various kinds of feedback to students. Here, I'll talk about just one kind of feedback - trait matching - and how it can be useful in the context of deliberate practice. I'll also offer some examples from my own pedagogy to show why having evidence is so powerful.

Help Students Identify Revision Priorities by Noting Missing Traits or Qualities

One type of feedback that students can give one another is called "trait matching" in Eli. Reviewers check boxes to indicate whether a specific feature is present in the draft. When I'm teaching, I use trait matching items to help students zero in on what is most important at a particular stage in their drafting process. Early on, for instance, it might be a main idea or thesis. Later on, it might be supporting details to develop an argument more fully.

In the review report, then, I get a result like this:

This tells me what percentage of reviewed drafts contained the four traits I have specified should be in each one. Notice that in this summary, most writers have included a summary of their own media use patterns. But fewer writers have made references to two secondary sources in these drafts.

This helps me to identify what I need to emphasize to the whole group, and it also allows me to evaluate each individual student's revision priorities as reflected in their revision plans (also in Eli). I know that at least 44% of those plans should list references to secondary sources!

Here's how I might convey these trends to students. First, I will reassure them that the patterns they've noticed agree with my own reading of their work. This let's them know that they can trust the feedback they are receiving from their peers:

Overall Comments

Overall, your review responses to trait matching items (the check

boxes) and scaled items (star ratings) are very good and accurate. I

did not find many instances where I disagreed with reviewers about

what they had seen in a draft or how well the writer had met one of

the criteria represented in the star ratings.

What this means: you can trust the feedback coming from your peers

about whether or not your drafts contain all the specified features.

Use these as you begin drafting to turn your attention to those

things that were not present or not as detailed as they could have

been.

Next, I'll try to interpret a bit and even pull out some good examples that they identified during their reviews (and which I think everyone can learn from):

Trait Matching - Summarizing Patterns, Including Detail,

and Analyzing

I'm happy to say that on the whole, folks did a good job summarizing

their own data. Almost everyone (88%) included a summary of media

use patterns and (85%) supported these with detailed evidence. Of

the few who were rated by peers as deficient in this area, they

often merely listed statistics and did not frame these in terms of a

pattern. The following example is modified, but shows what I mean:

List rather than summarize

"I sent 27 text messages on Wednesday and 41 on Thursday. I received 18 texts on Wednesday and 51 on Thursday."

Summarize, rather than list:

"My weekday texting activity seemed to depend on how much time I spent at work on a given day. On my day off, Wednesday, I sent just a little under twice the number of texts than I did on Tuesday, a day when I worked. I also received more texts on my off day, likely because I was engaged in longer conversations than I would be if I were at work."

See how example one is just the facts, while example two identifies

a use pattern that the facts support? That's a key difference.

But by far, the biggest shift most of you will make as you draft

your essays is from summarizing to analyzing. This makes sense, but

will be a challenge as you also need to incorporate secondary source

data. Note that only 68% of you "

Described the relationship between two or more patterns" and just

"65% provided evidence to explain the relationship between two or

more patterns." As I read the drafts, I'd put those numbers just a

little bit lower - you were generous with one another in your

reviews this time! :)

Of course, these are just my comments to the whole group. For individual students, I can drill down further and say something like this:

Thanks for providing a wonderful example of using evidence to support a claim. You are using primary source data well in this draft! Now, work on putting your primary source data in comparison with the secondary source - the trends reported in the Pew Internet report. Are your media use patterns similar or different than others' in your age group as reported by Pew?

Having this evidence makes all the difference when it comes to getting students to see a writing assignment as a way to identify what kinds of writing moves they need to improve (vs. those that they are doing well) and to practice those things in a deliberate way.

References

Kellogg, R. T., & Whiteford, A. P. (2009). Training advanced writing skills: The case for deliberate practice. Educational Psychologies, 44(4), 250–266.

Saturday, February 23, 2013

The (non)Book of Eli

There are many stories to tell about our motivations for creating Eli Review. One goes back to my dissertation research at Purdue, where I studied the way experienced teachers adapted to new technologies in the classroom. The headline from that study: technologies that support writing have pedagogies built into them. Often, those pedagogies clash with those the teacher has. The takeaway from this is straighforward, but hardly simple. Rhetorics can live not only in books and articles, but in machines and software. When they do, they can transform practice in powerful ways.

What would it mean for us to build rhetorics and pedagogies into our own writing environments? That has been one of the driving questions of my career. And so it is one of the stories behind Eli. Eli is not the first system I had a hand in creating to embody a theory of rhetoric. But it is, by just about any standard, the most successful attempt. Eli is used every day by hundreds or even thousands of teachers and students. More than all the people who've ever read an article or book chapter I wrote, to be sure. Likely more than all the people who've ever heard me speak about research, theory, or pedagogy.

Eli embodies many theories about the way writing works. Far more than I can usefully wedge into an article and still have the article remain coherent. In Eli's deep structure - the data formats that represent people, texts, and actions in the system - lie counterintuitive ideas about textuality that mash the ideas of Derrida, Barthes, and Iser together. Eli doesn't see texts that are part of reviews as coherent wholes. Rather, a text is a surface upon which the social actions of a review unfold. Texts provide an ability to index actions, relate them to one another, and provide a view of what would ordinarily be invisible social interactions back to writers, reviewers, and review coordinators. And while texts in Eli are palimpsests, they are also social actors of a sort. That is, we understand that over the course of a review, texts assume the agency of various human users for whom they stand in. And when I say we "understand" this, I mean we've built representations of review activity that explicitly support what, in Actor-Network Theory terms, are moments of inscription, enrollment, and interresement in the course of a review. We even have an algorithm for evaluating review success based on this progression, a novel measure of review *activity* rather than review comments or texts.

Eli also carries our ideas about how people learn to write. One radical one is that people can learn as much or more from reviewing work by others as they can by writing. Another, less radical thought for most writing teachers that is still difficult to act upon in a traditional classroom is that where writers *do* learn from writing, they do so most effectively from revision. Eli provides an environment where review can play a more prominent role in learning to write simply by making the coordination of review activity far easier and faster to do. Eli also provides an environment where writers can get more high-quality feedback more often, allowing more of their writing time to be spent on revising.

If Eli were a book, I could never get an editor to allow me to put all the ideas that make it work into one volume. It would appear to stray, to lose focus, or to vacillate wildly from the minutae of poststructuralist theories of language to the currently-in-fashion ontological perspectives of ANT to the pragmatic ideas of writing researchers like Britton and Hillocks. In Eli, they live as comfortably as an engine, drive train, and electronic ignition controls in a contemporary car, systems that stem from ideas of different eras, with different theories, all working seamlessly together.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)